Picture this: You have an important deadline looming, but instead of working on it, you find yourself endlessly scrolling through social media, cleaning out your junk drawer, or suddenly deciding it’s the perfect time to bake a complicated cake. We’ve all been there, stuck in the cycle of putting off tasks we know we should be doing. This isn’t just laziness; it’s often a complex psychological dance rooted in how our brains are wired, a phenomenon researchers at institutions like Stanford University study extensively.

Procrastination is the act of delaying or postponing a task or set of tasks. It’s different from simply resting or taking a necessary break. It involves voluntarily delaying something despite knowing there will likely be negative consequences.

This behavior is incredibly common, affecting a significant portion of the population at various times. While it might offer temporary relief, chronic procrastination can severely impact productivity, increase stress levels, and negatively affect mental health and overall well-being.

Understanding why we procrastinate isn’t about making excuses; it’s about gaining insight into the underlying psychological and neurological processes at play. This knowledge is the crucial first step towards changing the behavior.

In this post, we’ll delve into the brain science behind delay, explore the common root causes, and, most importantly, share science-backed strategies you can use to break free from procrastination’s grip.

What is Procrastination, Really?

At its core, procrastination is an “aversion-avoidance” conflict. We feel aversion to a task and avoid it to feel better in the moment. It’s often misunderstood as poor time management, but it’s more closely linked to emotional regulation than scheduling skills.

Procrastination isn’t monolithic. There are different types, such as perfectionistic procrastination (delaying out of fear of not doing it perfectly), overwhelmed procrastination (delaying because a task feels too big), and aroused procrastination (delaying until the last minute for a rush of adrenaline). Decision procrastination is also common, where delaying making a choice feels easier than committing.

The immediate feeling associated with delaying is often temporary relief or comfort. However, this is quickly followed by stress, anxiety, and guilt as the deadline approaches. This cycle can be emotionally draining.

The Brain Science Behind Delay

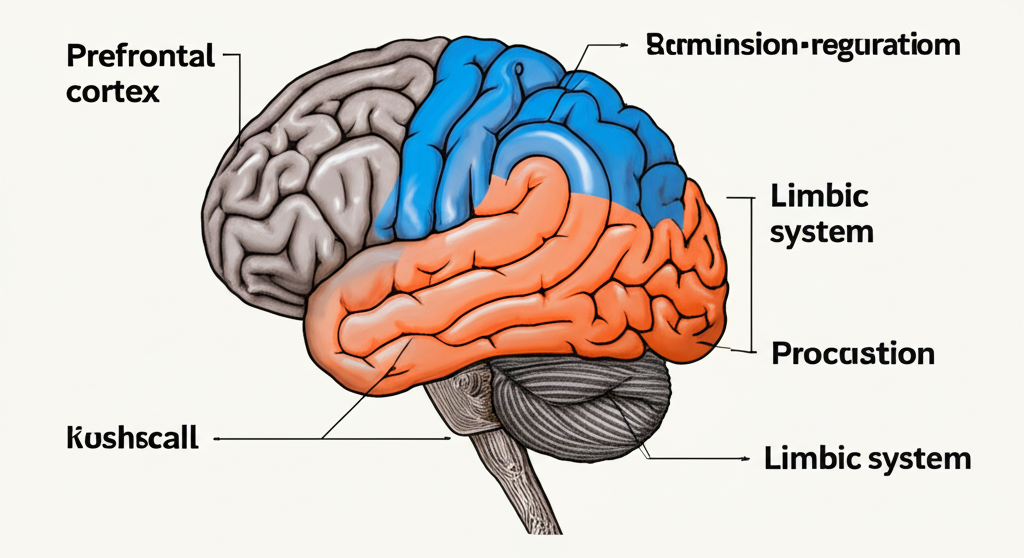

The Role of the Prefrontal Cortex

The prefrontal cortex (PFC), located behind your forehead, is the brain’s command center for executive functions. This includes planning, decision-making, impulse control, and focusing attention – all crucial for getting things done.

The PFC is constantly in a tug-of-war with the more primitive parts of the brain, like the limbic system, which seeks immediate comfort and avoids discomfort. The PFC is the long-term planner; the limbic system is the short-term pleasure-seeker.

When the PFC is fatigued or stressed, its ability to exert control over impulses weakens. This makes it harder to override the limbic system’s urge to avoid difficult tasks, leading to increased procrastination.

The Limbic System & Emotional Regulation

The limbic system, particularly the amygdala, plays a significant role in processing emotions like fear and discomfort. When we anticipate a difficult or unpleasant task, the amygdala can trigger feelings of anxiety or dread.

Procrastination, in this context, becomes a coping mechanism. By delaying the task, we temporarily avoid the negative feelings associated with it. This provides a moment of emotional relief, which the brain then reinforces, making us more likely to procrastinate again (“mood repair”).

The “Present Bias”

Our brains have a built-in “present bias,” also known as temporal discounting. This is the tendency to value immediate rewards or comfort more highly than future rewards or benefits, even if the future benefits are much larger.

The brain prioritizes the immediate feeling of relief from avoiding a task over the long-term satisfaction of completing it or avoiding future stress. The comfort of now outweighs the potential pain or gain of later.

This bias directly fuels procrastination. The discomfort of starting a task now feels more significant than the future positive outcome or avoidance of future negative consequences.

Why Do We Procrastinate? Common Causes

Fear is a major driver. This can be fear of failure, where not starting means you can’t fail, or even fear of success, where completing a task might lead to unwanted attention, new responsibilities, or disruption to your current life. Avoiding the task avoids the potential outcome.

Perfectionism is often linked to procrastination. If your standard is impossibly high, the fear of not meeting it can be paralyzing. The thought process is often “If I can’t do it perfectly, why start at all?” This ties self-worth to performance, making the risk of imperfection feel too great.

Tasks that are vague or seem overwhelming are prime targets for procrastination. When you don’t know exactly where to start or how to approach a massive project, your brain defaults to avoidance. This is linked to decision fatigue – having too many choices or unclear steps drains mental energy.

When you have low energy levels or are experiencing burnout, your willpower is depleted. The concept of “ego depletion” suggests that willpower is a finite resource (though this is debated), and fatigue certainly makes it harder for the prefrontal cortex to override the desire for rest and avoidance. Difficult tasks feel insurmountable when you’re tired.

Sometimes, the root cause is simply a lack of effective time management skills. Not knowing how to break down large tasks, estimate time needed, or integrate tasks into a schedule can make starting feel impossible.

Science-Backed Strategies to Beat Procrastination

Emotional Regulation Techniques

Understanding that procrastination is often about managing emotions means learning to tolerate discomfort is key. Mindfulness helps by allowing you to observe the uncomfortable feelings associated with a task (anxiety, boredom) without judgment, reducing their power over you.

Self-compassion is vital. When you procrastinate, avoid harsh self-criticism. Beating yourself up only increases stress and guilt, which further fuels the desire to avoid. Treat yourself with kindness; acknowledge the slip-up and gently redirect yourself.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Principles

CBT helps by identifying negative automatic thoughts that pop up about tasks (“This will be awful,” “I’m not capable”). Challenge these thoughts: Is it really awful? What evidence supports that thought?

Reframing tasks can make them less threatening. Instead of “Write a huge report,” think “Write the first paragraph.” Focus on progress, not perfection.

Habit Formation

Start with Tiny Habits, a method popularized by BJ Fogg of Stanford. Make the behavior incredibly small – so easy you can’t say no (e.g., “Put on my running shoes” instead of “Go for a run”). This reduces the activation energy required.

Use Habit Stacking: Link a desired new behavior to an existing habit (e.g., “After I pour my morning coffee, I will write one sentence of my report”). Focus on consistently doing the small action (the process), and the outcome will follow.

Task Management & Structuring

The Pomodoro Technique involves working in focused 25-minute intervals (Pomodoros) followed by short breaks. This leverages research on attention spans and prevents burnout. It breaks down work into manageable sprints.

Task Breakdown is crucial for large projects. Divide overwhelming tasks into the smallest possible, concrete steps. This makes starting feel less daunting.

Scheduling and Time Blocking involve assigning specific tasks to specific time slots in your calendar. This turns intentions into concrete plans, making them harder to ignore.

Optimizing Environment

Reduce external distractions by turning off notifications or closing unnecessary tabs. Create a dedicated workspace if possible, signaling to your brain that it’s time for focused work.

Make the desired behavior (working) easier – have your materials ready, computer open to the right document. Make the undesired behavior (procrastinating) harder – log out of social media, put your phone in another room.

The Power of Accountability

Telling a friend, colleague, or family member about your goal or deadline creates external pressure. Working alongside others (in person or virtually, known as “body doubling”) can also help maintain focus.

Using external deadlines, even self-imposed ones shared with others, is generally more effective than abstract goals.

Building Long-Term Resilience Against Procrastination

Becoming more self-aware is key. Pay attention to when and why you procrastinate. Identify your triggers, your go-to avoidance behaviors, and the feelings that arise before you delay.

Foster a growth mindset. Understand that your ability to manage tasks and overcome procrastination is not fixed; it’s a skill you can develop with practice and effort. View setbacks as learning opportunities.

Prioritize self-care. Adequate sleep, regular exercise, and good nutrition are foundational. They impact your energy levels, mood, and the cognitive function of your prefrontal cortex, directly influencing your willpower and ability to regulate emotions.

Finally, celebrate small wins. Acknowledging progress, no matter how minor, reinforces positive behavior and provides positive emotional feedback, counteracting the negative cycle of guilt associated with procrastination.

Conclusion

Procrastination is less about being lazy and more about a struggle with emotional regulation and cognitive biases like the present bias. Our brains are often wired to seek immediate comfort over future gain, making difficult tasks hard to start.

Overcoming procrastination is not a one-time fix but a learned skill. It requires patience, self-awareness, and consistent practice applying different strategies tailored to your triggers and the task at hand.

By understanding the science and implementing these techniques, you can gain greater control over your time, reduce stress, and achieve your goals more effectively.

FAQ

Q: Is procrastination a sign of laziness?

A: No, it’s generally viewed more as an issue of emotional regulation and difficulty tolerating discomfort associated with tasks rather than inherent laziness.

Q: Can procrastination be a sign of a mental health issue?

A: While not a mental health disorder itself, chronic, severe procrastination can be associated with or exacerbated by conditions like anxiety, depression, or ADHD. If it significantly impacts your life, consult a professional.

Q: Does waiting until the last minute help some people work better?

A: While some people feel they work better under pressure, research suggests that this often comes at the cost of increased stress and potentially lower quality work compared to starting earlier and working consistently.

Q: Are there apps that can help with procrastination?

A: Yes, many apps use principles like the Pomodoro Technique, task tracking, or environment blocking (like website blockers) to help structure work time and reduce distractions. Examples include Forest or Freedom.

Q: How long does it take to stop procrastinating?

A: There’s no set time frame. It’s an ongoing process of building self-awareness, practicing new habits, and learning to manage the emotions associated with tasks. Be patient and focus on making small, consistent improvements.