Introduction

Have you ever stopped to think about who invented the zipper, or why teabags are shaped like they are? Most of the items we use daily seem so simple, so… ordinary. Yet, many of these ubiquitous objects have fascinating, often surprising, histories tucked away, waiting to be discovered. They are far more than just functional tools; they are products of human ingenuity, born from necessity, sparked by happy accidents, and shaped by the times. These hidden histories tell compelling stories about our past, reflecting how we lived, worked, and communicated. We will delve into the surprising origins and evolution of several common items, exploring the ‘aha!’ moments and rocky roads that brought them into our lives. You might be surprised at the complex journeys of these seemingly simple things. Discover more about the things we use every day.

Why Everyday Objects Have Fascinating Pasts

Invention often springs from the need to solve a problem. Whether it was fastening clothes securely, sending messages efficiently, or holding papers together, solutions developed over time have become the commonplace items we rely on. The history of everyday objects shows us how these solutions were conceived and refined.

More Than Just Function

These objects are snapshots of changing lifestyles, evolving technologies, and shifting societal needs. Their stories offer a unique lens into human progress, sometimes revealing more about an era than grand inventions. A simple paperclip or postage stamp can reflect cultural values, economic pressures, or even acts of defiance.

The ‘Aha!’ Moments Behind the Ordinary

Many everyday items were invented by people you’ve likely never heard of, trying to fix specific issues. Their creations, often refined by others, quietly revolutionized daily life. It reminds us that sometimes the most impactful inventions are the ones we take for granted, seamlessly integrated into the fabric of our existence.

The Zipper’s Rocky Road to Success

The modern zipper is incredibly reliable, but its journey to ubiquity was anything but smooth. It required multiple inventors and decades of trial and error to perfect the design we know today.

Early Concepts and Failures

One early patent, for a shoe fastener, was granted to Elias Howe in 1851. While not a zipper, it showed similar ideas of interlocking mechanisms. Later, Whitcomb Judson patented his “Clasp Locker” in 1891, intended for boots. Judson’s device was complex, unreliable, and often came undone, preventing it from gaining widespread popularity.

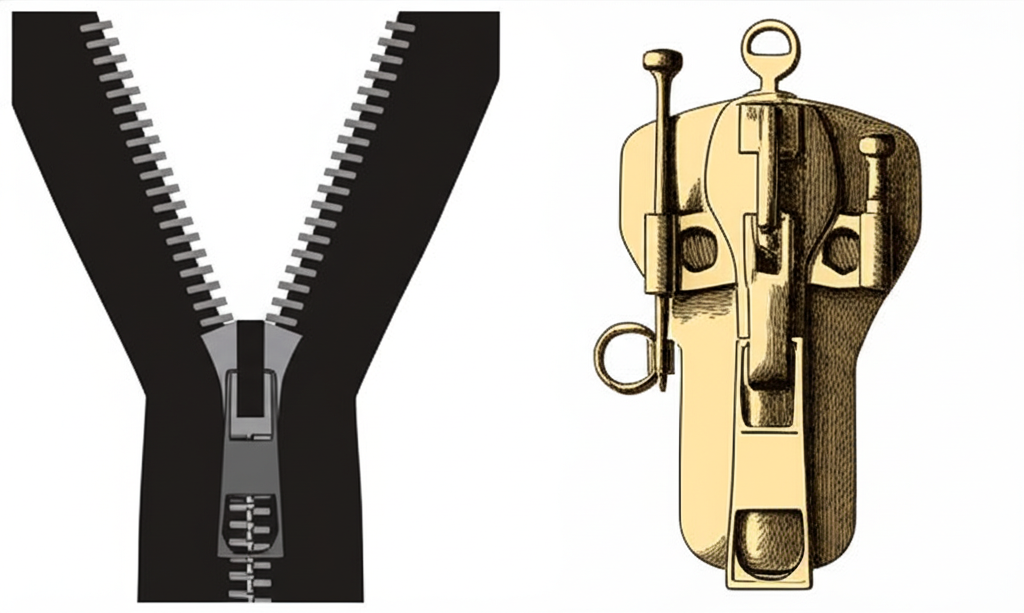

Gideon Sundback’s Breakthrough

The true breakthrough came with Gideon Sundback, a Swedish-American electrical engineer. Working for Judson’s company, Sundback significantly improved the design. By 1913, he had created the “Hookless Fastener No. 2,” featuring interlocking teeth and a slider mechanism. He refined this further into the modern form. BF Goodrich, a tire company, started using Sundback’s fastener on rubber boots in 1923 and coined the name “zipper” because of the sound it made.

Marketing and Adoption

Initially, the zipper found limited use on boots, tobacco pouches, and experimental clothing. The fashion industry was slow to adopt it, deeming it too crude. Its reliability was proven during WWII when it was used on flight suits and other military gear. This exposure helped it gain acceptance, and by the 1950s, the zipper had finally become a common household item used on everything from trousers to bags.

The Accidental Genius of the Teabag

The teabag is a simple, convenient invention, but its widespread adoption wasn’t initially planned by its creator. It became popular through consumer innovation.

Thomas Sullivan’s Marketing Gimmick

Around 1908, Thomas Sullivan, a New York tea merchant, started sending samples of tea to customers in small silk bags. He intended this as a cost-effective way to provide small quantities for tasting. His idea was that customers would open the bags and brew the loose tea leaves inside.

Consumers’ Creative Use

</br/>

Instead, many customers, perhaps misunderstanding the purpose or finding it easier, simply dropped the entire silk bag into hot water. They discovered this method was convenient and still produced a decent cup of tea. This unintended use by consumers quickly became the preferred way to brew small portions, essentially inventing the teabag as a brewing device.

Evolution of Materials and Design

The early silk bags were not ideal for brewing. Manufacturers soon switched to more porous materials like gauze, and eventually to paper filter bags, which allowed water to circulate better. Over time, various shapes were introduced, such as square, round, and pyramid shapes, each claiming different benefits for tea diffusion and flavor.

The Humble Paperclip’s Norwegian Saga

The paperclip seems like the most basic of inventions, yet its history is surprisingly debated and even holds cultural significance, particularly in Norway.

Pre-Paperclip Solutions

Before the common wire paperclip, people used various methods to keep papers together. These included tying ribbons through pierced holes, using straight pins, or even applying wax seals. These methods were often time-consuming, damaged the paper, or were less secure.

Early Designs and the Gem Clip

Several inventors patented devices for holding papers in the late 19th century. However, the most widely used design, the double-oval “Gem” clip, was never patented. It is believed to have originated in Britain around the 1890s, possibly by Gem Manufacturing Ltd. It quickly became popular due to its simplicity and efficiency.

Johan Vaaler’s Patent (and why he didn’t invent the Gem)

A common misconception credits Norwegian inventor Johan Vaaler with inventing the paperclip. He did patent a paperclip design in 1899 and 1901, but his design was less functional than the Gem clip, essentially just a bent wire loop with pointed ends. Despite not inventing the popular design, Vaaler’s patent became a point of national pride in Norway.

Symbol of Norwegian Resistance

During WWII, under Nazi occupation, Norwegians were forbidden to wear buttons or badges displaying the king’s monogram. As a subtle act of nonviolent resistance, many Norwegians began wearing paperclips on their lapels. It symbolized unity (“we are bound together”) and resistance against the occupying forces, giving the simple object a profound cultural meaning.

Sticky Situations: The Story of Adhesive Tape

From sealing boxes to quick repairs, adhesive tape is indispensable. Its widespread use stems from the ingenuity of a scientist at a major manufacturing company.

Richard Drew’s Problem Solving

Richard Drew was a young engineer at the 3M Company in the 1920s. While working with automotive painters, he noticed they had trouble creating clean lines between colors. He developed a masking tape with adhesive only on the edges, creating the first Scotch® Masking Tape in 1925.

The Birth of Transparent Tape

During the Great Depression, people were looking for cheap ways to mend torn items. Drew saw the need for a more general-purpose adhesive tape. He developed transparent cellulose tape (later known as Cellophane Tape or Scotch® Tape) in 1930. It offered a simple, versatile solution for repairing everything from books to clothing.

Innovations and Variations

The success of transparent tape led to the development of numerous variations for specific tasks. This included packing tape, electrical tape, duct tape, and more. The original “Scotch” nickname allegedly came from a customer complaining that Drew’s early masking tape was “too Scotch” (a slur implying stinginess), referring to the initial lack of adhesive coverage, which Drew later corrected. Today, adhesive tape is a multi-billion dollar industry.

From Postage to Philately: The Stamp’s Journey

Communicating over distance was historically slow and expensive. The invention of the postage stamp revolutionized this, making correspondence accessible to the masses and even spawning a popular hobby.

The Need for Postal Reform

Before postage stamps, sending mail was complicated and costly. The recipient, not the sender, usually paid, and the cost varied based on distance and the number of pages. This system was inefficient and discouraged communication for many. Rowland Hill, a British educator and inventor, proposed a radical reform.

The Penny Black and Penny Blue

Hill’s proposal, the Uniform Penny Post, suggested a single, affordable rate regardless of distance, paid for by the sender. To facilitate prepayment, he invented the adhesive postage stamp. The world’s first adhesive stamps, the Penny Black (featuring Queen Victoria’s profile) and the Two Penny Blue, were introduced in the UK in 1840. This simple system made sending letters affordable and predictable.

Impact on Communication and Society

The introduction of prepaid postage dramatically increased the volume of mail, boosting literacy and facilitating personal and business communication. The concept quickly spread globally, transforming postal systems worldwide.

The Rise of Stamp Collecting

Almost immediately after their introduction, people began collecting stamps. This hobby, known as philately, grew in popularity, with collectors valuing stamps for their design, history, and rarity. It remains a popular pastime today, connecting people to history and geography through these tiny pieces of paper.

The Ubiquitous Rubber Band

Simple, stretchy, and incredibly useful, the rubber band is another item whose specific origin is often overlooked, despite its presence in almost every home and office.

Stephen Perry’s Patent

While rubber had been known for centuries, harnessing its elasticity for practical items took time. The specific invention of the rubber band, as we know it, is credited to Stephen Perry of Messrs. Perry & Co., rubber manufacturers in London. He patented the rubber band in England in 1845. His patent described using vulcanized rubber (a process developed by Charles Goodyear just a few years earlier) to create elastic rings.

Manufacturing Process

Modern rubber bands are typically made by extruding rubber into long tubes, curing the rubber (often with heat), and then slicing the cooled tubes into thin bands. Different rubber compounds and curing processes result in varying elasticity and durability.

Endless Uses and Cultural Impact

The rubber band is a prime example of a simple invention with near-infinite applications. It is used for fastening, bundling, securing, and countless improvised uses daily. Its adaptability and low cost have made it a truly ubiquitous tool across industries and households globally. It serves as a perfect reminder that fundamental utility can come from the most basic materials and designs.

The Unseen Threads Connecting Us to the Past

We’ve explored just a few examples, but the hidden histories of everyday objects are everywhere. The zipper’s bumpy development, the accidental brilliance behind the teabag, the paperclip’s unexpected role in wartime resistance, the problem-solving origins of adhesive tape, the revolutionary impact of the postage stamp, and the simple utility of the rubber band.

These stories remind us that history isn’t confined to textbooks or grand events. It’s embedded in the things we touch and use every single day. Innovation, whether planned or accidental, often begins with the desire to make life slightly better, easier, or more efficient. Looking closely at the ordinary can reveal extraordinary tales of human creativity and resilience. Next time you zip up a jacket, staple papers, or brew a cup of tea, pause for a moment and appreciate the journey that simple item took to get to you.

FAQ

Q: Who invented the zipper?

A: While earlier attempts existed, the modern, reliable zipper is largely credited to Gideon Sundback, who perfected the design in the early 20th century.

Q: Was the teabag invented on purpose?

A: Not exactly. Tea merchant Thomas Sullivan sent tea samples in small silk bags, intending customers to empty them. Customers started brewing the tea while still in the bag, leading to the teabag’s popularity.

Q: Did Johan Vaaler invent the paperclip?

A: Johan Vaaler patented a paperclip design in 1899, but it was different from the ubiquitous “Gem” design. The Gem clip, which is most common today, was likely developed and manufactured in Britain around the same time and was never patented.

Q: Where does the name “Scotch” tape come from?

A: The name “Scotch” was initially applied to 3M’s masking tape. Legend says a customer complained about the early tape not having enough adhesive across the whole strip, calling it “Scotch,” a term then used to imply stinginess. 3M later embraced the name for its transparent tape line.

Q: How did the postage stamp change things?

A: Before the postage stamp, mail was expensive and paid for by the recipient. The stamp, introduced by Rowland Hill in the UK, allowed the sender to prepay at an affordable, fixed rate, making communication much more accessible and increasing mail volume dramatically.