Introduction

Look around you. How many zippers can you spot? On your jacket, your bag, your shoes, maybe even your pillowcase? They’re everywhere, a fundamental part of modern life, used countless times each day without a second thought. This simple mechanical device is so ubiquitous, we rarely pause to consider its origins or the journey it took to get here. Have you ever stopped to think about who invented this simple yet ingenious device and how it came to be so common?

The truth is, the history of the humble zipper is far more complex, challenging, and often overlooked than you might imagine. It wasn’t a single flash of inspiration but rather a long, arduous process involving multiple inventors, significant failures, and decades of struggle for acceptance. From flawed early concepts to a global necessity, the zipper’s path was anything but straightforward.

This article aims to explore the full, fascinating story of this everyday engineering marvel. We will delve into the world before zippers, examine the early attempts and their shortcomings, highlight the pivotal breakthrough that made it reliable, trace its slow adoption, and witness its eventual triumph as an essential component of modern life.

The World Before Zippers: A Fastener Famine?

Before the late 19th century, fastening things shut was a far more laborious affair. Our ancestors relied primarily on methods like buttons, laces, hooks and eyes, and simple ties or drawstrings. These traditional fasteners served their purpose, but they came with significant limitations that became increasingly apparent as the pace of life and manufacturing accelerated.

Consider the inefficiencies: fastening a row of twenty buttons or threading and tying multiple sets of laces was time-consuming. These methods were also prone to failure – buttons could snap off, laces could fray and break, and hooks and eyes might pop open unexpectedly. This was particularly frustrating for tasks requiring quick access or secure closure. Furthermore, manipulating small buttons or tying laces could be difficult for certain individuals, such as young children, the elderly, or those with limited dexterity.

The growing industrial age, with its emphasis on speed and efficiency, highlighted the need for something better. Clothing and goods needed faster, more reliable, and easier-to-use closure methods that could also provide a more secure seal than gaps between buttons or loosely tied laces. The stage was set for a new kind of fastener, even if no one quite knew what it would look like.

Early Visions and Persistent Failures: The First Attempts

The idea of an automated or continuous closure method wasn’t new. As early as 1851, Elias Howe, the inventor more famous for perfecting the sewing machine, received a patent for an ‘Automatic, Continuous Clothing Closure’. His concept involved a series of clasps linked on a cord that could be pulled together. It was an intriguing mechanical notion with potential applications for clothing, bags, or other articles needing quick fastening.

Despite its innovative design, Howe never commercially marketed this invention. He was preoccupied with establishing and defending his highly successful sewing machine business, which demanded all his focus and resources. His early fastener concept remained largely undeveloped, a forgotten footnote in the history of closures.

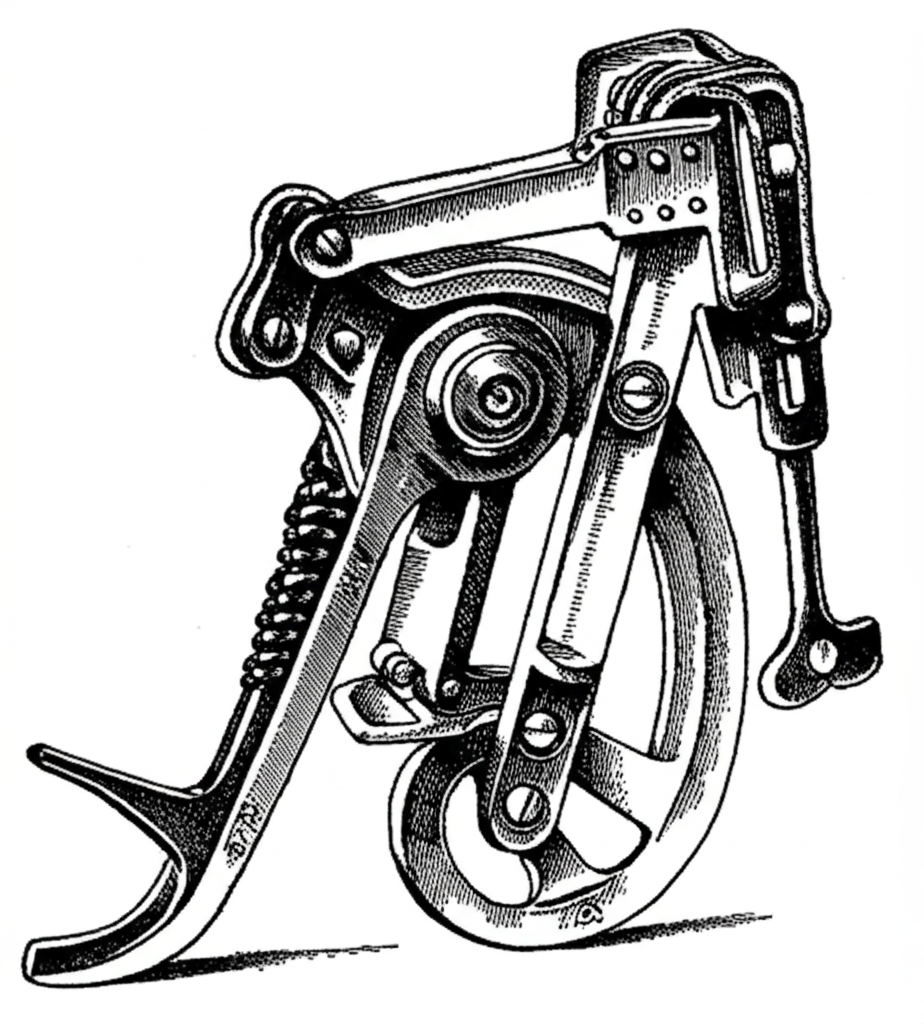

Fast forward to the late 1800s, and another inventor, Whitcomb L. Judson, stepped onto the scene. Driven by the desire to create a fastener that could quickly secure boots without tedious lacing, Judson patented his ‘Clasp Locker’ in 1891. This device was a complex system featuring rows of hooks and eyes on opposing fabric strips, which were joined by a movable ‘guide’ or ‘locker’ mechanism – the direct ancestor of the modern zipper slider. Judson debuted his invention at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and formed the Universal Fastener Company to promote it.

However, Judson’s ‘Clasp Locker’ proved to be a significant commercial failure. The intricate mechanism was unreliable; it frequently jammed, the hooks and eyes often popped open unexpectedly under tension, and manufacturing the precise components consistently at scale was difficult and expensive. Despite Judson’s persistent efforts and several improved patents over the following years, his fastener never achieved widespread acceptance due to its inherent flaws. It was a visionary idea that simply didn’t work well enough in practice.

The Breakthrough: Gideon Sundback and the ‘Separable Fastener’

Hope arrived in 1906 when the Universal Fastener Company hired Otto Frederick Gideon Sundback, a Swedish-American electrical engineer. Sundback was tasked with improving Judson’s troubled ‘Clasp Locker’. Rather than merely tweaking the existing design, Sundback embarked on an iterative process of fundamental re-engineering, eventually moving away entirely from Judson’s hook-and-eye concept.

Sundback’s crucial insight was the idea of interlocking teeth. He experimented with various shapes and arrangements. His 1913 attempt, known as the ‘Plako’, used hooks and eyes that were more stable, but it still had reliability issues. Undeterred, Sundback continued refining his design, leading to his major breakthrough in 1914, patented in 1917, which he called the ‘Separable Fastener’.

This design featured uniform, scoop-shaped metal elements (the teeth) crimped onto the edges of two fabric tapes. The genius lay in the slider, which had Y-shaped channels. As the slider moved, it forced the teeth on the left and right tapes to interlock snugly, creating a strong, continuous closure. To open, the slider’s tail separated the channels, pulling the teeth apart. This design was fundamentally superior because the interlocking elements provided much greater reliability, smoother action, and were far less likely to pop open under stress compared to the earlier hook-and-eye systems.

While the ‘Separable Fastener’ was a technical triumph, bringing it to market wasn’t easy. Manufacturing the thousands of small, precise, and uniform metal teeth required for each fastener presented significant engineering and production challenges that Sundback also had to overcome.

Naming the “Zipper” and Finding a Market

Despite Gideon Sundback’s technically superior design, his ‘Separable Fastener’ didn’t immediately take the world by storm. Its adoption was slow, hampered by its novelty and the previous failures of Judson’s version, which had created a perception of such devices as unreliable gadgets. Early uses were primarily limited to niche applications where quick closure was highly valued, such as rubber boots (galoshes) and tobacco pouches.

A pivotal moment came in 1923 when the B.F. Goodrich Company licensed Sundback’s fastener for use on their new line of rubber boots. A Goodrich executive, Harry Earle, was reportedly struck by the sound the fastener made when opened and closed. He coined the catchy, onomatopoeic name “Zipper,” and the boots were marketed as having a “zipper fastener.” This name stuck, becoming the common term for the device and eventually applied retroactively to Sundback’s invention itself.

The fashion industry, however, was initially resistant. Designers viewed the metal fastener as too utilitarian, even ugly, compared to elegant buttons or delicate laces. Acceptance gradually began in the late 1920s and early 1930s, starting with children’s clothing, where the ease of use was a clear advantage. A crucial breakthrough in high fashion occurred in the mid-1930s when designers like Elsa Schiaparelli began incorporating visible zippers into dresses and garments, using them as decorative elements rather than just hidden closures, challenging established norms. The final turning point came in the late 1930s when zippers were widely adopted for men’s trousers, replacing buttons for the fly. This application significantly boosted public acceptance, normalized the zipper, and removed its novelty or ‘gadget’ stigma, paving the way for its widespread use.

Wartime Demand and Post-War Dominance

World War II proved to be an unexpected but powerful catalyst for the mass production and standardization of the zipper. The conflict created an urgent and massive demand for durable, reliable fasteners for military applications. Zippers were needed for a vast array of items, including soldiers’ uniforms, flight suits, parachutes, tents, sleeping bags, duffel bags, and various equipment bags.

The military’s strict performance requirements pushed manufacturers to improve production efficiency, enhance quality control, and experiment with different materials beyond just metal, anticipating future needs. The sheer scale of wartime production forced companies to invest heavily in machinery and develop streamlined processes. This intense period of development and manufacturing not only met the military’s needs but also built the infrastructure, technical expertise, and production capacity necessary for producing zippers in vast quantities.

When the war ended in 1945, the established production lines and accumulated knowledge were perfectly positioned for the post-war economic boom. The industrial capacity that had churned out zippers for military gear quickly pivoted to meet burgeoning consumer demand. The result was an explosion in the use of zippers across countless industries – from ready-to-wear clothing, luggage, and handbags to furniture, sporting goods, and camping equipment. The zipper rapidly transitioned from a novel convenience to an expected feature, cementing its place as an essential part of modern life.

The Modern Zipper: Types, Manufacturing, and Global Impact

Today, the zipper is an invisible ubiquity, manufactured on a truly staggering scale. It’s hard to imagine the world without it. While Gideon Sundback’s basic principle remains unchanged, modern technology and material science have led to a diverse range of zipper types, each suited for specific applications.

Here are the most common types:

- Metal Zippers: Made from brass, aluminum, or nickel teeth. Known for durability, strength, and a classic aesthetic. Common in denim, leather jackets, and heavy-duty bags.

- Coil Zippers: Constructed from continuous coils of nylon or polyester monofilament forming the teeth. Flexible, lightweight, cost-effective, and the most common type globally, found in most clothing, bags, and upholstery.

- Plastic Molded Zippers: Feature individual teeth molded from durable plastic resins like Delrin or Vislon. Strong, weather-resistant, often chunkier in appearance. Used in luggage, outdoor gear, sportswear, and items needing corrosion resistance.

- Invisible Zippers: Designed to disappear into the seam of a garment for a smooth, seamless look. Primarily used in dresses, skirts, and formal wear.

Other variations include water-resistant/waterproof zippers with special coatings or tapes, separating zippers (like those on jackets that detach at the bottom), and two-way zippers that can open from either end. Modern manufacturing involves high-speed, automated processes capable of producing millions of miles of zipper chain annually with incredible precision.

The global zipper market is dominated by a few key players. The YKK Group (Yoshida Kogyo Kabushikikaisha) is famously prevalent; its initials are often seen on zipper pulls worldwide. YKK’s dominance stems from its commitment to quality, highly efficient and vertically integrated manufacturing (they even smelt their own metals), vast distribution network, and continuous innovation. The scale of the industry is immense, highlighting the zipper’s transformation into a low-cost, high-volume commodity.

Unzipping Facts: Interesting Trivia and Oddities

The history and mechanics of zippers hide some truly fascinating details:

- The Name: As mentioned, “Zipper” was coined by B.F. Goodrich executive Harry Earle in 1923, inspired by the sound of the slider on boots. The term quickly became synonymous with Sundback’s device.

- YKK’s Scale: YKK is estimated to produce enough zipper chain each year to circle the Earth multiple times – potentially over 1.2 million miles annually!

- Basic Mechanics: The slider is essentially a Y-shaped wedge that forces the interlocking elements together on one side and separates them on the other using two channels.

- Unusual Applications: Zippers have been used in surprising places, including the closures on early space suits (requiring airtight seals) and various medical devices.

- Pull Tab Design: The shape and design of the small tab you grab can vary wildly, offering opportunities for branding or ergonomic improvement, but the core function remains the same – providing leverage for the slider.

- Why Zippers Break: Common culprits include jammed fabric caught in the slider, worn or missing teeth, bent sliders, or issues with the insertion pin on separating zippers. Many minor jams can be fixed!

- Early Fashion Show: Elsa Schiaparelli’s decision to feature bold, colored zippers prominently on her couture in the 1930s was a deliberate act to modernize fashion and challenge the status quo, causing quite a stir.

Conclusion: Celebrating an Everyday Engineering Marvel

The journey of the zipper is a remarkable testament to human ingenuity, persistence, and the often-unseen complexity of everyday objects. It began as a simple idea to improve upon tedious traditional fasteners, navigated through decades of flawed designs and commercial failures by visionary inventors like Whitcomb L. Judson, and finally found its reliable form thanks to the meticulous engineering of Gideon Sundback.

From its slow adoption in niche markets to its catchy new name and eventual embrace by the fashion world and military necessity, the zipper’s path to dominance was long and challenging. Today, this seemingly simple mechanical device has fundamentally changed not only how we fasten our clothes but also countless other products, bringing unparalleled convenience, speed, and reliability to modern life.

So, the next time you effortlessly zip up your jacket or bag, take a moment to appreciate the hidden history, the persistent efforts of its inventors, and the ingenious engineering behind this unsung hero – the fascinating and ubiquitous zipper.

FAQ

Who is credited with inventing the modern, reliable zipper?

Gideon Sundback, a Swedish-American engineer, is widely credited with inventing the “Separable Fastener” in the 1910s, which is the basis for the reliable zipper we use today.

Why did early zipper designs fail?

Early designs, like Whitcomb L. Judson’s ‘Clasp Locker’, failed primarily because they were mechanically unreliable. They often jammed, broke, or popped open unexpectedly due to complex hook-and-eye systems that lacked the smooth, secure interlocking of Sundback’s later design.

How did the zipper get its name?

The name “Zipper” was coined in 1923 by Harry Earle, an executive at the B.F. Goodrich Company, who licensed Sundback’s fastener for rubber boots. The name was inspired by the “zip” sound the fastener made.

What are the main types of zippers used today?

The main types are metal zippers (durability, classic look), coil zippers (flexible, common, lightweight), plastic molded zippers (strong, weather-resistant), and invisible zippers (designed to be hidden).

Why are YKK zippers so common?

YKK Group’s dominance is due to their high-quality manufacturing, vertical integration (controlling the entire production process), vast global distribution network, and reputation for reliability, making them a preferred supplier for many manufacturers worldwide.